![]() ( Source: kimwoojong )

( Source: kimwoojong )

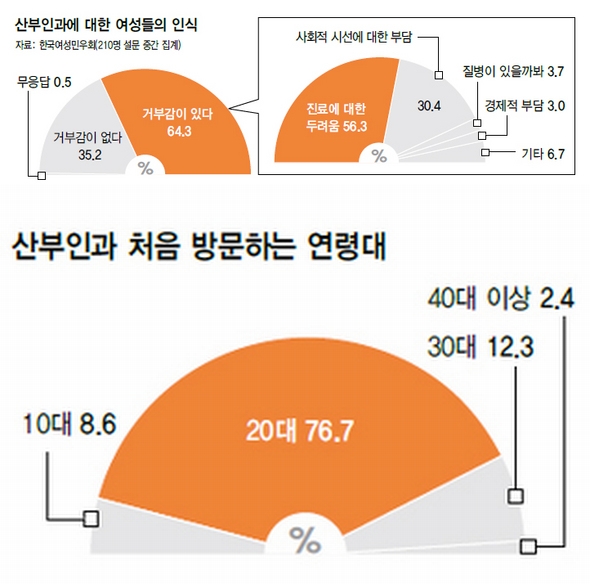

Introduction

While the Korean public seems to lack any sense of urgency about it, raising Korea’s extremely low fertility rate looks set to become one of Korea’s most pressing economic issues in the next decade or so, and being able to witness events unfold as various vested interests contest the wrenching changes to Korean workplace culture, welfare, immigration policy and gender roles that will have to be made to do so is just one reason why the study of contemporary Korean society is so interesting.

Another is that developments here will to a greater or lesser extent be repeated in almost all developed countries a little later, generally with less dire figures at the moment but still well below the replacement level of 2.1 births per woman of reproductive age (see the graph below). Policymakers, academics and economists around the world will soon be paying much more attention to Korea for that reason, but for now, as always, Japan’s similar situation dominates international discourse, media-friendly stories about new robots designed to help care for Japan’s aging population probably serving more to exoticize and distance the issue more than draw attention to Western countries’ similar impending problems. Ironically, that will mean that the Korean government’s policy of doing too little too late will come to have even more relevance for them.

![]() ( Source. See here for tables )

( Source. See here for tables )

Beginning with my own summary of the issue here, I wrote a glut of posts on this issue in the first few months of the blog. But after a certain point there’s only so many different aspects of the problem you can outline, and in the last, lame-duck year of what had already been a very incoherent and ineffectual Roh Moo-hyun Administration overall, few changes were going to be made to the central and local Korean governments’ inadequate, short-term and/or one-off cash incentives and tax-breaks for couples to have children too (see here for examples of those). But now six months after the inauguration of Lee Myung-bak, it’s high time to examine what changes have taken place under a new administration.

If you can forgive the brief aside for a moment, that’s partially to better understand the subject for its own sake, and to tie up some loose ends from those earlier posts, and partially because I plan to start discussing recent events and developments on the blog much more often in the future, albeit only those related to my niches of Korean gender issues, women and men’s body images, advertising, feminism, sexuality and so forth. I’ll wisely discuss that (slight) blogging-related change more at a later date; for now, lets just say that as I’m trying to make more posts more academically rigorous and defensible, then I’m finding that the research and writing for posts like this and this is starting to take weeks rather than days, and I still want to keep readers interested and entertained while I’m buried in my books.

But before I get to specific policy changes in later posts, first in this post I’ll discuss the following report on the economic effects of Korea’s low birth rate by Kim Woo-young in the Korea Herald. I chose it because It’s a good (re)-introduction to the topic for anyone unfamiliar with it, and coincidentally published on the same day that my second child was born, but on the other hand also because it’s so trite, reading as if all the instances of “Korea” in it could be replaced with almost any other developed country but still have just as much (ir)relevance to their situations. Korean society does have some very specific features that combine to make the its birthrate one of the lowest in the world, but either these are not given enough emphasis in the article or aren’t even mentioned at all, and so in an earlier draft of this post I was constantly linking to my earlier post to cover the gaps. Instead, let me just recommend that interested readers go on to read that in full after this.

Given that the notoriously user-unfriendly Korea Herald makes articles subscriber-only after a week or so too, then for the sake of providing a resource I’ll reproduce it here in full rather than give excerpts, adding my own comments as I go along.

![]() ( Source: Yume Love )

( Source: Yume Love )

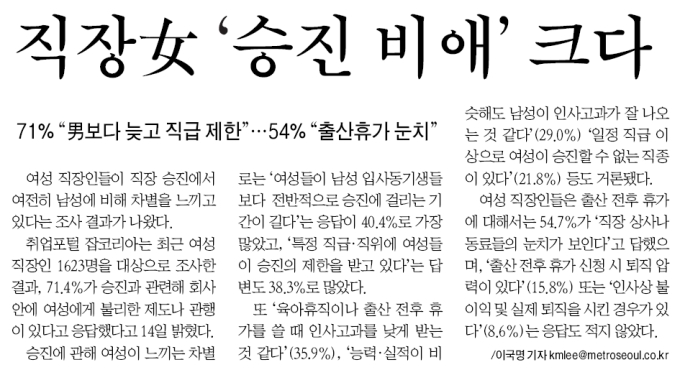

[KOREA`S ECONOMIC CHALLENGES (7)] Declining fertility poses challenge to economy

(This is the 7th in a 20-part series analyzing major challenges to the Korean economy and suggesting mid- to long-term strategies to improve the economic fundamentals and the efficiency of economic policies. The articles, to be published once every week, are contributed by economists at the Bank of Korea`s Institute for Monetary & Economic Research. – Ed.)

In Korea, the total fertility rate – the average number of children born to a woman over her lifetime – continuously declined from the late 1950s to 2005. The TFR dropped from 4.53 in 1970 and 2.83 in 1980, then to 1.59 in 1990 and 1.08 in 2005. It rose slightly, to 1.13 and 1.26 in 2006 and 2007, respectively, boosted by the “Twin Spring Year” and the “Year of the Golden Pig.” It is uncertain, therefore, whether the latest trend will continue or revert to a decline.

As for why there was a boost in 2007, see here. That that was only a temporary blip was confirmed by the National Statistical Office on Thursday, which stated that “the number of newborn infants totaled 35,400 in June, down 1,800 or 4.8 percent from the same period a year earlier. In the first half, a total of 240,700 babies were born, compared with 244,400 a year before.” Meanwhile, the number of marriages is down 4.1% from the same period a year ago, and divorces up by 4.7% (reported in the Korea Herald, p.5, but strangely not posted to its website).

The fall in Korea`s fertility rate has been steeper than in other countries. It decreased by 3.45 from 1970 to 2005; it fell by 2.26 in the world as a whole during the same period. At the time, it fell by 0.87 in Japan, 0.41 in the United States and 0.63 in the United Kingdom.

In conjunction with economic development plans, Korea rigorously promoted a government-led birth control policy. Despite a birthrate below the ideal rate of 2.1 in 1983, the policy was maintained until 1996. In 2002, the problem of low fertility began attracting public attention. The government responded to the low TFR only after it dropped to the lowest level internationally. Accordingly, the government has been criticized for its sluggish response.

Statistics on the low Korean fertility rate abound, but all are essentially useless without reference to their sources, and providing those surely doesn’t seem to be too much to ask of a full-page report in a national newspaper? Moreover, once new policies to deal with low fertility begin to have greater financial impacts on individuals and companies (or even if existing legislation on maternity leave and so forth was actually enforced), then I imagine that greater statistical rigor will be required to defend both the evidence for their need and of their later successes, in much the same way that the climate-change “debate” has evolved.

Another similarity to climate-change politics is that there is an overwhelming consensus by both the government and academia that Korea’s demographic situation is dire and urgent action must be taken, but the former is unwilling to pay the political costs in imposing financial costs on the public to deal with them, particularly with Korea’s low tax, family-based, minimalist welfare system. That may sound rather cynical of me, but then consider the recent reactions around the world to increasing taxes on petrol/gasoline, essential if CO2-emission reduction targets are to be reached: it’s easy to be an environmentalist if it doesn’t involve any cost to you personally.

( Source: yusheng )

That slight tangent aside, the birth-control policy referred to above is known as the “Family Planning Program” (FPP), begun in 1962, and bringing the per capita rate of new births from 6.0 in 1960 to 1.6 in 1988. The article paints an inaccurate, excessively dogmatic picture of various governments’ adherence to it: while it did indeed officially end in1996, in practice it was “virtually extinct” in social discourse and government rhetoric by the 1980s, and no more official support for social programs aimed at lowering the birth rate was provided after 1988 (Kim: 352). Having said that, the FPP was somewhat more than providing leaflets on contraception at doctors’ clinics, probably the first image that comes to Western-readers’ minds: in fact, in its intrusiveness, ruthlessness and virtual state control of citizens’ reproductive lives, it was arguably outdone only by the infamous one-child policy of China. Lest you feel that that’s an exaggeration, then how else to describe a policy that at the height of the Cold War regularly withdrew forces from the DMZ to help deliver condoms, implant IUDs and perform (strongly encouraged) sterilizations on citizens living in rural areas and outlying islands?

I’ll cover the FPP in great detail in Part Five of this series next month. Before then though, a very overdue Part Three will be up in the next few days.

Women`s participation in the labor market and fertility rate

The female labor force participation rate in Korea – as a percentage of the population aged 15 and older, both employed and unemployed – increased from 39.3 percent in 1970 to 50.2 percent in 2007. In the same period, the men`s labor force participation rate decreased from 77.9 percent to 74.0 percent.

The increase in female workforce participation seems to be connected with the decline in the total fertility rate. The rise in labor force participation of women of childbearing age is notable. The labor force participation rate of those aged 25-29 increased markedly, from 32 percent in 1970 to 68 percent in 2007. Among those age 30-34, it also increased substantially, from 40.8 percent to 53.6 percent in the same period. Figure 1 shows that women`s labor force participation has a negative correlation with the fertility rate.

Not included in the version at the Korea Herald website, I took a picture of the accompanying graphs from the newspaper itself, forgetting that my wife’s computer problems meant that I couldn’t upload it sorry. Again then, a mention of the sources for them would have been nice.

Declining fertility rate

![]() ( Source: ThisParticularGreg )

( Source: ThisParticularGreg )

A number of social, economic and psychological factors are attributed as the cause of the declining fertility rate. A decrease in the fertility rate can arise not only from a fall in the rate of married women giving birth but also from an increasing number of single women who don`t want to get married.

I didn’t understand that last point for quite a while, but now I take it to mean that because Koreans are so reluctant to have children out of wedlock (to put it mildly), then a decrease in the marriage rate would indeed result in a corresponding decrease in the fertility rate. By coincidence, yesterday I happened to come across a table of “2002 births to mothers aged 15-19 per 1000 women aged 15-19 in OECD countries” (Baker: 73), and Korea came dead last with 2.7, quite some distance from even Japan with 6.2. Not that that’s not a good thing, but it’s undoubtedly related. By comparison, Sweden had 6.9, France 11.4, Germany 13.2, New Zealand 14.0, Australia 18.4, Canada 21.9, the UK 28.6, the US 43.0, and finally Mexico topped the table with 51.1.

The average number of children born to married women declined from 4.1 in 1970 to 3.0 in 1990, and then to 2.4 in 2005. Also, women are having children later in life. The proportion of the 20-24 age group in the total number of women giving birth dropped from the mid-1980s onward, and that of the 25-29 age group also decreased from the late 1980s. However, the portion of women in their 30s giving birth began increasing in the mid-1980s. A decrease in childbearing by women in their 20s, even when coupled with a rate increase in among women in their 30s, usually leads to a reduction in childbirth due to health issues.

The decline in the total fertility rate outweighs that of the average number of children born to married women, since the number of married women has declined. Since the total fertility rate statistics include both married and single women, the decrease in the fertility rate becomes more significant because of the fall in the number of marriages and the decrease in the average number of children born to married women.

Anybody else not quite understand that last paragraph?

The proportion of married women in the 20-24 age group decreased from 42.8 percent in 1970 to 6.3 percent in 2005. In the same period, the number of married women aged 25-29 declined from 90.3 percent to 40.9 percent. Among those aged 30-34, it dropped from 98.6 percent to 81.0 percent. Meanwhile, the mean age of first-time brides verifies that women are delaying marriage, as the age increased from 24.8 years in 1990 to 27.8 years in 2006. Many single women postpone marriage as they extend their education and become financially independent.

![]() ( Source: Sinfest )

( Source: Sinfest )

We can categorize the main factors in the decline of the fertility rate of married women into economic reasons, changes in family values and social factors. According to a survey by the Chungnam Women`s Policy Development (published in January 2006), the reasons why married women avoid childbirth are the impediments to their social activities imposed by childbirth and child care, the need for freedom in their lives, the cost of children’s education, and difficulties in family circumstances.

As for the economic factors, the costs of child rearing and of education are the ones most mentioned. According to a family income survey by the National Statistical Office for urban households with more than two family members, the share of educational expenses in average monthly consumption expenditures rose from 7.7 percent in the 1981 to 12 percent in 2007. The proportion of income that goes into food, however, declined from 51.5 percent in 1981 to 25.1 percent in 2007.

These are amongst some of the paragraphs that most bugged me. Nothing in them is incorrect per se, but could be applicable to any country because of sloppy wording. Obviously the cost of children’s education would be the most mentioned factor, more important in Korea than in most other countries, and if that’s not obvious, then see this post. Which is precisely my point: it’s not unreasonable for readers to assume that “the cost of children’s education” means buying supplies and so forth like in, say, New Zealand, but in fact it almost exclusively means the cost of going to after-school institutes.

If you can get a hold of it, I highly recommend reading Jae-Kyung Lee’s chapter “The Social Construction and Contradiction in the Mothering of Working Class Women” in Feminist Cultural Politics in Korea, for an interesting discussion of the precise costs involved. Based on interviews of working-class women in Bucheon and Incheon (industrial cities close to Seoul) in April 2003, it’s amazing to see how central their children’s education at after-school institutes is to their lives, despite taking up quite an considerable part of their family’s meager incomes.

Job insecurity and low income have become one of the primary reasons for not having children. The increasing number of temporary workers has caused job security to deteriorate, while the wages of temporary and casual workers are lower than those of permanent workers. Temporary workers made up 30.4 percent of male workers and 42.7 percent of female workers in 2006. The wages of temporary workers are only 62.8 percent of those of permanent workers.

Again quite true, but needing more elaboration and emphasis. Although again the above statistics are somewhat meaningless, and I’ll be investigating figures from various sources in Part Four of this series soon (Part Three up next week), Korea went from having the most, male-breadwinner jobs-for-life in the OECD (those where the man’s income and frequent side benefits were sufficient to support a nuclear family) in 1997 to the least in 2007, something that has fundamentally changed Korean working life and family life.

It is well-known that when a female temporary worker wants maternity leave, she is very likely to be given notice of dismissal. The 2007 payment status of maternity protection benefits shows that only 66 temporary workers out of a total of 58,000 female workers took maternity leave. This reveals that female temporary workers have difficulties in getting maternity leave. For example, one company upgraded the temporary status of female workers to permanent status in 2007. After obtaining permanent employment status, their applications for maternity leave increased dramatically. Thus, employment security does seem to have a positive effect on decisions about whether or not to have children.

Rather than continuing to make trite, overly generalized points about educated women having less babies, the “double burden” and more meaningless statistics, to put it mildly the author should have elaborated that first point much more. He makes it sound positively normal, whereas surely the effects of minor things like the complete non-enforcement of legislation on Korea’s fertility rate make all other factors pale in comparison?

It also reminds me that, even before I read that, I found that the overall tone of this piece was to present fertility decline is presented as almost some inexorable force of nature inherent to modernization, ignoring both the huge differences that a country’s ranking on the Gender Empowerment Measure makes – there is a huge difference in fertility rates between Northern and Southern Europe for instance, proving that women’s levels of political and economic empowerment are more crucial than “previous statistical association[s] between high fertility, Catholicism, and traditional family values” (Baker: 71) – and the fact that in many other developed countries, where trivial things like maternity leave legislation is actually enforced, then the decline in the fertility rate has been slowed or even reversed.

Changes in family values also seem to affect childbirth. According to the 2005 National Survey of Marriage and Birth Rates, 35 percent of married woman said that they have no plans to have children. Some 17.5 percent of single men and 26.2 percent of single women expressed their intention to remain single. Half of single women 35 or older did not want to get married for many reasons, including the burden of child rearing. The results reflect sweeping changes in family values.

( Source: yusheng )

A social atmosphere in which work and household management are incompatible is also cited by many women. Despite the increase in women`s economic participation, women are required to take responsibility for household chores and childcare. In addition, a return to work after giving birth is not guaranteed, and women therefore have difficulties in deciding whether to have children. According to the study “The Low Fertility Situation and Responses” published in March 2006 by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, more than half of working women experienced difficulties in maintaining their working career with pregnancy and in returning to work after giving birth. A shortage in childcare facilities that parents can trust also inhibits married women from having children. While the total number of childcare facilities increased from 9,085 to 28,367 between 1995-2005, that of government-established and public nursery facilities rose only slightly – from 1,092 to 1,473. It is clear that the government needs to better support the child care sector.

Again, “a shortage in childcare facilities that parents can trust” begs some questions, and understates the problem. In my earlier post, I discuss that in more detail, mentioning the regularity with which reports of kindergarten students becoming ill after being fed bad food appear in the Korean media, and the fact that the relevant ministries are so understaffed that they can rarely if ever make inspections of facilities.

For more specific information on numbers of childcare facilities, see pp.19-20 of the Word Document the following link will open: http://www.utoronto.ca/ai/canada-korea/papers/Yeong-RanPark_FamilyPolicy.doc.

Demographic changes

As the fertility rate has decreased, population growth has also slowed, and the population is expected to start declining in 2019. Population growth, which stood at 3.01 percent in 1961 and 2.21 percent in 1970, dropped to only 0.33 percent by 2007.

According to population projections by the National Statistical Office, the population growth rate will fall to -1.71 percent by 2050. However, the development of medical technology has greatly-extended life expectancy – from 62 years in 1970 to 79 in 2006.

The decline in the fertility rate and the increase in life expectancy have accelerated the aging of Korean society. The percentage of the population aged 65 and older increased from 3.1 percent in 1970 to 9.9 percent in 2007. Korea has already become an aging society, with 7 percent or more of its population 65 and older in 2000, and is expected to become an aged society (with 14 percent or more at 65 and older) in 2018. Korea is also forecast to become a super-aged society (with 20 percent of its population at 65 or older) by 2026.

The percentage of the population age 14 or younger fell from 42.5 percent in 1970 to 18 percent in 2007, and is anticipated to decline further to 8.9 percent in 2050. The proportion of the so-called “productive population,” aged 15 to 64, is predicted to shrink from 72 percent in 2007 to 53 percent by 2050.

The changing population structure has a number of effects on the economy. Representative effects can, for example, include a drop in labor supply and an increase in the burden of supporting older people.

Growth in the number of productive population has declined continuously, and this may lead to a labor supply shortage. The productive population grew by 3.44 percent in 1970, but this rate has since dropped to 0.57 percent in 2007 and is forecast to begin to decline from 2018. The percentage of middle-aged workers in the economically active population is meanwhile likely to increase, and a disparity between supply and demand by age group is therefore also anticipated.

Solutions

Is it a proper solution for Korea to raise the fertility rate to prevent the population from declining further? Let us suppose that the decline in the fertility rate, and the aging of society, which we are now experiencing, is a procedure for adjusting the population to its optimal level. If, after adjusting our population to its appropriate level, we can maintain an optimal fertility rate level, population decline will not be a big problem in the long run. If the fertility rate remains too low, however, even after the appropriate adjustment, this can impact on the economy.

Looking at the Korean economy, we observe that the production structure has, since the early 1990s, changed into one that is less labor intensive. While the number of employees increased at an average annual rate of 4 percent until the early 1990s, it has dropped to 1 percent level since the start of this decade. The ratio of employment to GDP – the number of workers needed per 1 billion won of GDP – decreased from 47 in the 1990s to 35 in the 2000s, a phenomenon attributable to increased labor productivity. The improvement in labor productivity means labor demand is sluggish or even declines if the economy does not continually expand.

![]() ( Source: DarkRoastedBlend )

( Source: DarkRoastedBlend )

Examining this in more detail, we can see in Figure 4 that the ratio of employment to GDP has fallen over the years. Most notably, in the manufacturing sector it plunged drastically from 253 in 1970 to 18 in 2006. In the case of the service industry, in contrast, it dropped from 74 in 1970 to 41 in 2006. The reduction of the employment to GDP ratio in the service sector was less than that of the manufacturing industry. Despite the increasing employment in the service sector, by absorbing labor force from the manufacturing sector, a large part of service facilities still remained relatively small and its activity was restricted only to the domestic market.

Looking at the production structure of the manufacturing industry until 1991, output in the labor-intensive industries surpassed that in the capital-intensive industries. Since 1992, however, output in capital-intensive industries has exceeded that of the labor-intensive ones. Although total manufacturing sector employment began to decline from 1992, total sector output has constantly increased, meaning “growth without employment.”

Thanks to technological development, labor productivity in Korea is forecast to continuously improve. If the labor productivity in the service sector is improved, overall labor demand is likely to fall in the future. A reduction in the labor supply is thus necessary to a certain extent. If the labor supply shrinks at a faster pace than labor demand, we resolve the problem by raising the labor force participation rate, which as of 2007 was 74 percent among men and 50 percent among women.

Is labor productivity in Korea indeed “forecast to continuously improve”? By whom? Given that Koreans work some of the longest hours in the world, but have extremely low productivity, then any statements like that need to be taken with a grain of salt. In practice, while Koreans do indeed spend a great deal of time physically present at their workplaces, and have a much-exaggerated reputation for hard work as a result, this is merely a vestige of the work mentality of Korea’s previously secure jobs-for-life, where contracts were meaningless and ambitious employees could not be seen to leave before the boss did, regardless of how little work they actually had to do. Hence the extra hours that supposedly lazier Westerners don’t work are often spent simply napping or chatting on the internet instead, as can be confirmed by visiting virtually any Korean white-collar company after lunchtime.

( “Labor compensation per employee, total economy, Average annual growth in percentage, 1995-2006 or latest available period”. Source: Left Flank )

For more on that, read here and here. Needless to say, only being at work from 9-5 would both raise Korea’s labor productivity and make raising children much easier. Certainly that would still not quite be enough, as things like Western companies’ recent moves to flexitime systems demonstrate, but the shift would trigger a veritable social revolution in Korea.

As the population is aging, the number of the elderly whom the productive population needs to support has increased. Between 1970 and 2007, the dependency ratio more than doubled from 5.7 percent to 13.8 percent. In other words, the number of people aged over 65 has increased from 6 to 14 per 100 productive people. That means a tremendous increase in the burden on the productive population.

The rapidly aging society does not only cause increasing financial burden, however. It has positive effects on the economy at the same time. In Switzerland, for example, according to research by the Swiss National Science Foundation, grandparents spend 100 million hours per year taking care of their grandchildren, and the economic value of this amounts to $1.9 billion. The elderly help create jobs such as patient care assistants in the service sector.

The elderly have played a role in promoting women`s labor force participation and thereby in raising married women`s fertility rate. The elderly has taken on the household chores and child care, and in this context the aging population has made some contributions to Korea`s economy.

Well, yes, and New Scientist magazine has noticed a strong positive correlation between the proximity of grandparents and the number of children a couple has, and there is strong evidence that menopause evolved at least partially to free women to be good grandmothers too, but the article ignores the fact that, these days, Korean grandparents are increasingly reluctant to spend their retirements taking care of grandchildren (virtually every book I have on that generation of Koreans mentions that). There are indeed still many “weekend parents” in Korea (similar to “weekend couples”), forced by inadequate childcare options to sometimes drive their children to their grandparents’ houses M-F and only seeing their children on weekends, but that mindset shift of grandparents means that they are less and less common. Besides, they were always measures of last resort, and the many accounts of heartbroken, crying mothers on the drive back home every Sunday night that I’ve read demonstrate that they were hardly a natural, “Neo-Confucian” feature of East Asian societies anayway. But with even that fallback option removed then now there’s even more excuse for couples to have less or no children.

Policy suggestions

The economy is an organism, and we might want to allow the fertility rate to adjust naturally, to maintain our population at the optimal level. The fertility rate which remains very low, however, is undesirable, as it could increase population volatility. The government should therefore conduct a policy to raise the fertility rate to prevent the population from shrinking rapidly.

Given that many avoid marriage because of the financial burdens of childbirth and childcare, policy measures are required to boost childbirth among married women and encourage single women to get married.

Local governments have introduced policies to encourage childbearing such as cash benefits a short period of time after childbirth. The effects of the policy may be limited, however, and we need to develop policies which will have long-lasting effects. The central government has pursued a number of policy options, including the revision of the Enforcement Decree of the Employment Insurance Act, the childbirth credit system for pension funds, and taxation reform. Such policies will need to be strengthened and promoted constantly.

The aging population and the rising financial burden have become a reality. If we deploy measures to help the elderly contribute to the economy, however, we may be able to prevent the financial burden on the younger generation from growing too heavy.

As always, a much longer post than intended! In not this post but the next, I’ll cover childbirth in Korea itself, discussing how notions of modernization and Korean women’s body images have combined to lead to high incidences of such things as high rates of unnecessary Cesarean sections here and even of pregnant women dieting. Neither are confined to only Korean women by any means, but given everything else I’ve said about Korean women’s body images and so forth, then I do strongly expect that my research for it will show that both will be much more common than in Western countries.

____

Baker, Maureen Choices and Constraints in Family Life, 2007.

Kim, Eun-shil, “Women and the Culture Surrounding Childbirth”, in Korean Anthropology: Contemporary Korean Culture in Flux, Anthology of Korean Studies Volume III, ed. By Korean National Commission for UNESCO (2003), pp. 343-371. Originally in Korea Journal, vol. 37, no. 4 (Winter 1997), downloadable here.

( Source:

( Source:  (

(

( Source:

( Source:  ( Source:

( Source:

(

(